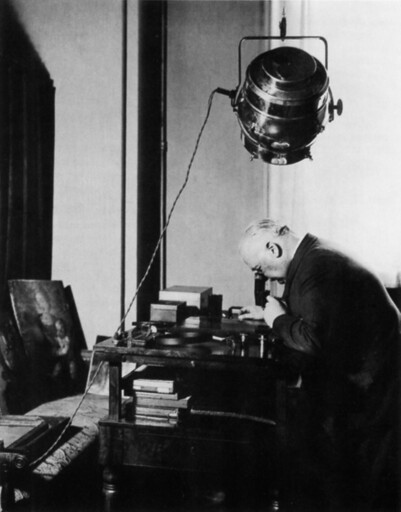

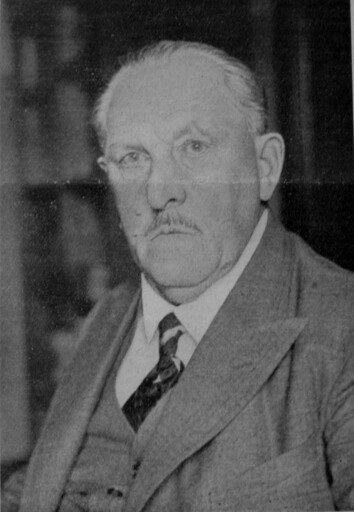

Soon afterwards Max Doerner (1870–1939) succeeded in turning Gräff’s objective into reality. Himself a painter, the author of the seminal publication The Materials of the Artist and Their Use in Painting and professor for painting technology at the Academy of Fine Arts, he drew up plans in 1934 for the ‘Reich Institute for Painting Technology’ based on ideas put forward by Gräff and Eibner. It was founded in 1937 as the ‘State Test and Research Institute for Painting Technology’, with the addition of the name ‘Doerner Institut’, with departments for physical chemistry, painting technology and art history. Doerner became the director of the new institute that was housed at 3, Leopoldstrasse, next to the Academy of Fine Arts. As a ‘Reichsinstitut’ – a government organisation under the Nazis – it came under the immediate authority of the ‘Reich Chamber of Fine Art’. The early history of the institute was marked by National Socialism. It was opened on 19 July 1937, on the same day as the ‘Degenerate Art’ propaganda exhibition. In the post-war period little was undertaken to review this period in history. Only the important discovery in 2005 of all files related to the Doerner Institut during the whole of the Third Reich, as well as other documents from recently acquired bequests, enabled and instigated the reconstruction of the institute’s history and the pivotal role played by its founding father. In his book of 2016 The Fight for Art. Max Doerner and his Reich Institute for Painting Technology (series of publications brought out by the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen in böhlau Verlag) Andreas Burmester provides a meticulously researched insight into the microcosmos that was the institute under the control of the Reich Chamber of Fine Art, the Reich Chamber of Culture and, consequently, the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. The publication however covers a greater time span, ranging from 1910 until the mid-1950s – from the end of the German Empire to World War I, from the Weimar Republic to the early years of the Third Reich, World War II and the bombing of Munich, and from the period of de-Nazification and the beginning of re-building to life in a democratic state.

The central figure in the first few years was Max Doerner. Burmester describes him as a gifted artist of Bavaria’s alpine foothills, as an extremely modest, solitary ‘fighter’ figure afflicted by a number of illnesses. At the same time he was a charismatic teacher of a whole generation of artists, admired without reservation by his pupils, hated by his opponents. In his institute, the complexities of the founding period were followed by years of fruitful activity on a variety of topics, including a regulatory work on artists’materials, in particular: following the ‘signs of deterioration of the system era’ German artists should finally be given everything they need to know so as to avoid the mistakes in painting made in the 19th century. Other subjects covered the identification of forgeries – including of works by Guardi, Spitzweg and what was supposedly a Raphael for Hitler – as well as prominent restoration projects in Naumburg and at Wartburg Castle. Adolf Ziegler, in the eyes of leading Nazi figures the aritst who embraced their ‘ideology’, was discovered and endorsed by Hitler and was responsible for the ‘degenerate art’ campaign in the second half of the 1930s. Doerner’s death in 1939 gave him the opportunity to claim the direction of the Doerner Institut for himself. He proceeded to fire ‘uncomfortable’ members of staff without delay, robbing the institute of much talent and steering it towards a dark future up until his detention in Dachau concentration camp in 1943. Changes to regulations governing artists’ materials that were ‘essential to the war effort’, the quest for substitute materials during the wartime economy, assisting the ‘Ahnenerbe’ (ancestral heritage; a research facility run by the SS), art-technological research on cultural property ‘appropriated’ by the Reichsleiter Rosenberg Taskforce, and plans for a restoration class for artists with war disabilities were determining key tasks carried out until the end of the war. The study of painting technology research and its mastery as a sign of artistic quality was all too easily instrumentalised for Nazi ideology propaganda. While Max Doerner had already battled against art without painting technology, Adolf Ziegler misappropriated this to revile contemporary artists as ‘incompetent’.